The office was quiet save for the clicking of fingers upon a keyboard. The secretary was busy at work, transposing minutes from a recent meeting onto the computer. Just days before, the secretary discovered that her husband was cheating on her, so the busy work she had in front of her was a welcomed relief from her thoughts. I was in her company, and I sat quietly studying my Swahili book. Our chairman was seated in his usual chair in the next room, shuffling through files or reading the daily paper. Things proceeded peacefully along.

Suddenly the manager storms in, breaking the office's peace like a rock thrown into a still pond. He comes in with the usual smile and first greets me, asking how the morning was and discussing his concern for the late rains. When finishing with me, he briefly greets the secretary, and then moves into the next room where he showers the chairman with the whole arsenal of salutations, as if they had not seen each other for months. After the long greeting session, the manager returns to the office with a small stack of papers and he tosses them over the secretary's busy fingers. “Type this,” He commanded flatly. The secretary returned his gesture with a deep glower, obviously bothered by the lack of respect in his demeanor. She quietly removed her new stack of work from the keyboard where they blocked her from continuing her current assignment, and as she set it aside her computer, the manager turned to her and said, “And have it done by today.”

Enough. I felt her anger swell, involuntarily moving her to speak. She began like this, “Why do you treat me like this? What have I done to you?” Her voice rose with emotion as she continued, switching languages to her more comfortable Swahili. She stormed into the chairman's office, her recent workload gripped firmly in her hands, and she began to plead her case in front of him. The manager joined them in the next room, and a full argument erupted.

I saw it coming. Tensions had been high for over four months between the two members of this organization, and it was only a matter of time before this verbal confrontation. It started when the manager made sexual advances upon the secretary, but was refused outright. In turn, a passive-aggressive battle to exert his dominance over her ensued.

I could not understand the conversation in the least. As the voices rose in volume, they increased in tempo, spewing long chains of Swahili sentences even a trained ear could have difficulty with. Then, from nowhere I heard the manager break into English, stating, “But chairman, She's a woman. She's a lesser sex. I cannot take her seriously.”

Wow. Up to this time I had never heard a single racist, tribalist, or sexist comment from the manager. I always saw him with an amicable smile and a willingness to please. It was shocking to hear those words spoken from his lips, and the words reverberated in my head.

To say such a thing in a workplace in America is an instant firing, and perhaps a lawsuit.

The reaction from the chairman was almost condoning. It was as if “She's a lesser sex” is a perfectly valid reason to treat someone the way he did. The secretary's frustration manifested into tears, and she stormed out of the office despite the chairman's attempts to console her. The manager emerged from the chairman's office with a grin and an air of victory about him. The muscles in my arms tightened and my fists clenched tight, aching to release themselves upon the manager's contrived smile.

I'm sure if the secretary had one wish, it would be to have her husband stop cheating on her, or at least to not have caught her husband cheating on her. The burden of her personal life was made known only to me and her select friends, none of whom work in the office. And knowing her entire story, I empathized deeply.

For the first time, I felt the tragedy of being a woman in this society. In the secretary's tears I felt a small piece of the heavy weight of subjugation a working woman has to bear in the presence of men; men who were raised with a sense of entitlement over their female counterparts. To be shattered emotionally, to be oppressed openly, and to be culturally obligated to endure, this secretary demonstrated clearly that women here are a far cry from the lesser sex.

Friday, March 25, 2011

Friday, March 11, 2011

Peace

It is midday in a large, Kenyan town. Matatus, buses and three-wheeled taxi cabs litter the small stage. Above the puttering, idle engines touts scream, “Nairobi? Nairobi!” to anyone who passes by. The peripheries are lined with small, makeshift stands from which mamas sell mangoes, bananas, and fresh-made honey in glass liquor flasks. Suddenly, piercing shouts fill the air – the Swahili word for “Thief!! Thief!!” rings out clearly over the general commotion. The shouts seize my attention and I turn my head to see a fleeing young man and a stampede of pursuers. People pour in from all sides and cut off potential exits for the young juvenile. He flees into a small shop made of corrugated metal, and apparently the shop owner is a friend or acquaintance, because the shop owner prevents anyone else from entering. The shop owner undoubtedly knows the havoc that could ensue inside his shop should he leave the juvenile to the crowd. Slowly the people disperse, and the young man is left with the guilt and shame of all his peers. The swift action of mob justice is incomparable.

The world is a dangerous place. Before coming to Africa, I was certain the entire continent was riddled with civil unrest, unstable political systems, riots, uprisings, and all the other things that are showcased on CNN. Rebellions in Libya are in the Kenyan news these days, and recent conflicts between Egypt, Israel, and oil have flared up. Even Kenya's neighboring country Somalia suffers a constant state of turmoil. Just the other day, a Kenyan school and health facility on Somalia's border had to shut down because bullets were found in and around the area, bullets that were fired in Somalia which flew across country lines.

But Kenya is peaceful. Anyone I speak with about the Kenyan culture always lists their peaceful nature as one of their most valued traits. Though Kenya is very political, the new constitution last August found no serious violence, especially in the rural areas. And as the story above displays, any foul play among this country's citizens is not tolerated.

But apart from nature, peace and safety in my village is unparalleled. I feel safer in my village than I felt in the suburbs of Southern California where I grew up. My neighbors are the most friendly, most caring people I could have hoped for and if it weren't for the small children entering my room and touching all my stuff, I would feel completely comfortable leaving my door wide open while I'm gone. The people take care of each other here, and when they ask “Where are you going?” all the time, I realize it is not because they are nosy or rude but more because they know where to find you should you be needed or should a problem arise. In the village I could send books or packages with matatu drivers, and I have 100% confidence they will reach their destination.

Once I left my guitar with a new friend who was to bring it to me after a short while. After arriving very late, he noticed my anxiety and asked me if I was worried he wouldn't bring it to me. He then assured me that he would not steal, that in fact he could not. And the longer I stay here, the more I realize the truth of his words – the people in my village are unable to steal. The level of safety and peace is inundated so deeply into their culture.

And not just political and social peace. There's a kind of overwhelming serenity that seizes me in the rugged, natural beauty where I live. To the west, massive hills stagger into the distance, gently fading from sight like a visible echo. Vast plains stretch themselves until the horizon and continue beyond, lit brightly by the sun – save for dappled shadows from the puffy low-hanging clouds. In the mornings, the sunlight can pour over the hills, as if to make the trees sing with life and youth. The evenings bring the most inspiring sunsets, as the incandescent sun shares its vibrant colors to the entire horizon. On moonless nights, the Milky Way divides the center of the sky and even the shyest of stars dimly twinkle, as if for the first time. The full moon can come over the hills like a sunrise, soaking in all the starlight and illuminating the entire landscape with its sublime glow. Birds chirp and flit about in the trees, merrily going about building their nests or wooing their playmates. The air is clean and fresh, and with just one full breath I feel like I am satisfied for the day. Often I am stopped on the road by the overwhelming beauty of this place, and in those moments I want to live here forever.

Maybe I will live here forever.

The world is a dangerous place. Before coming to Africa, I was certain the entire continent was riddled with civil unrest, unstable political systems, riots, uprisings, and all the other things that are showcased on CNN. Rebellions in Libya are in the Kenyan news these days, and recent conflicts between Egypt, Israel, and oil have flared up. Even Kenya's neighboring country Somalia suffers a constant state of turmoil. Just the other day, a Kenyan school and health facility on Somalia's border had to shut down because bullets were found in and around the area, bullets that were fired in Somalia which flew across country lines.

But Kenya is peaceful. Anyone I speak with about the Kenyan culture always lists their peaceful nature as one of their most valued traits. Though Kenya is very political, the new constitution last August found no serious violence, especially in the rural areas. And as the story above displays, any foul play among this country's citizens is not tolerated.

But apart from nature, peace and safety in my village is unparalleled. I feel safer in my village than I felt in the suburbs of Southern California where I grew up. My neighbors are the most friendly, most caring people I could have hoped for and if it weren't for the small children entering my room and touching all my stuff, I would feel completely comfortable leaving my door wide open while I'm gone. The people take care of each other here, and when they ask “Where are you going?” all the time, I realize it is not because they are nosy or rude but more because they know where to find you should you be needed or should a problem arise. In the village I could send books or packages with matatu drivers, and I have 100% confidence they will reach their destination.

Once I left my guitar with a new friend who was to bring it to me after a short while. After arriving very late, he noticed my anxiety and asked me if I was worried he wouldn't bring it to me. He then assured me that he would not steal, that in fact he could not. And the longer I stay here, the more I realize the truth of his words – the people in my village are unable to steal. The level of safety and peace is inundated so deeply into their culture.

And not just political and social peace. There's a kind of overwhelming serenity that seizes me in the rugged, natural beauty where I live. To the west, massive hills stagger into the distance, gently fading from sight like a visible echo. Vast plains stretch themselves until the horizon and continue beyond, lit brightly by the sun – save for dappled shadows from the puffy low-hanging clouds. In the mornings, the sunlight can pour over the hills, as if to make the trees sing with life and youth. The evenings bring the most inspiring sunsets, as the incandescent sun shares its vibrant colors to the entire horizon. On moonless nights, the Milky Way divides the center of the sky and even the shyest of stars dimly twinkle, as if for the first time. The full moon can come over the hills like a sunrise, soaking in all the starlight and illuminating the entire landscape with its sublime glow. Birds chirp and flit about in the trees, merrily going about building their nests or wooing their playmates. The air is clean and fresh, and with just one full breath I feel like I am satisfied for the day. Often I am stopped on the road by the overwhelming beauty of this place, and in those moments I want to live here forever.

Maybe I will live here forever.

Tuesday, March 1, 2011

My Hair (Religion)

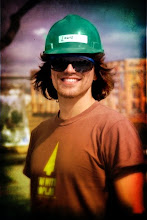

It has been 10 months since I cut my hair. Although it is culturally taboo for men to have long hair, I explain to people that I want to grow it for donation. My father is Italian and has a uni-brow, and my cute Asian mother has the thickest, blackest hair one could ever hope for, so I was doomed from conception with a luscious head of hair. I think the little girl or boy who receives it will be much appreciative.

But this post has nothing to do with my hair. This post is about Jesus Christ. And money.

The Kenyans are highly religious. When coming to Kenya, I did absolutely no background research, so I assumed the religions were tribal and pagan. I expected people to worship the sun god, and during religious gatherings cut themselves to spill their blood on the soil. Instead, I came to find the normal religions: Christianity and Islam. And Christian missionaries hit Kenya especially hard. I can only guess at how it happened: the shiny beacons of hope and light (white people) came with their money and built fancy churches and gave people money and food if they converted to Christianity. So undoubtedly all the starving people were on their knees in front of murals of Jesus Christ.

So as a result, there is no escape from religion in Kenya. On the coast, Muslim dress-code can be seen on every other woman: the flowing black burka concealing any beauty or sensual body curve which God endowed a young woman (in all honesty, I think those mysterious Muslim women are intriguingly beautiful..though I have no way of knowing). On public buses, often a christian pastor will stand in the front aisle and preach for a full-length, hour sermon and then proceed to gather 'offering' from the bus' customers. Angry-sounding pastors gather up their most grizzly voices and shout from the televisions on Sunday mornings, and everyone's customizable ring tones play the latest popular worship song. So there is no question this culture is inundated with religious symbols and rituals, no debate that people could see a poster of someone in a white robe holding a lamb and not instantly think of Jesus.

But back to my hair. The front of it reaches past my eyes, and the back nearly covers my neck entirely. In addition to my unkempt, borderline culturally inappropriate head of hair, my laziness usually allows my goatee to grow for a month or longer. All of that in combination with my caramel, middle-eastern skin makes me closely resemble a certain messiah-- namely Jesus Christ. To confirm this, when visiting the Christian groups at the secondary school, whispers spread like wildfire among the girls as I walked in, saying, “Anafanana na Yesu!” or “He looks like Jesus!”

And in my village, this is how I am treated. People think I am their Savior, that I have come to alleviate them from their poverty and physical suffering. Just like the Jews expected Jesus to be a great political leader who would save them from the Romans, the people in my village expect something so different from me. But Jesus had so much more in mind. He came to save humanity from themselves, to free people from the burdens of their own corruption.

I realize that it is highly arrogant and borderline blasphemous to compare myself to Jesus Christ. Whether you believe He was truly God Himself, an inspirational hippie philosopher, or a fictional character in a giant storybook, I pale in comparison. But upon reflection, my life here in Kenya draws some parallels to Jesus' life on this Earth. To name a few:

Wherever Jesus walked, multitudes would gather around. His mere words stirred inspiration and excitement among his listeners, his knowledge as a child surpassed that of the church leaders, and miracles sparked from his fingertips. Similarly, wherever I walk, people stop what they are doing and shout greetings and welcomes. With my guitar in hand, children flock and gather, eagerly listening to anything I would play. My computer with its internet capabilities gives me an “infinite knowledge,” and with my fancy camera, it is like I miraculously capture life itself.

So in my village there is no doubt I am special. Just my skin color gives me away as something “different,” “exciting” and “worth looking at.” And people's expectations of me are unbounded. In their minds, I am capable of doing everything. One of those main expectations is that of sourcing money from either myself or my wealthy friends, and putting that money into their pockets.

I came, not to give money, but as a medium for people to better their lives. I came to teach whatever I know and to share my life and my experiences to anyone interested. I came to bring a sense of work ethic and empowerment, that through hard work and struggle their lives may be changed. But people want money. They ask me for jobs even after I tell them I am a volunteer, and they ask me to write proposals for them even after I explain why I cannot. The people here see me with the same misunderstanding the Jews had when they saw Jesus. And because I do not offer money, food, or will not take their baby to America with me when I return, I am just as easily dismissed.

But back to religion. When I first arrived in Kenya, I sat through a three-hour church session where people sat in rapt attention, and danced without reservation during the entire period. I was astounded at their stamina and thought to myself how they must really love God and serve Jesus. But the longer I stay, the more I realize people here who call themselves “Christian” or “Muslim” are not really worshiping God. They worship money. They worship all the things that come with money—comfort, status, popularity, sex. They are just like most Americans.

Televangelists preach here in Kenya about wealth in Jesus' name, and America is revered for their prosperity, often to be claimed as a nation “Blessed by God.” A fine, upstanding “Christian” will just as likely double the price in the market to naïve tourists as would their non-religious countrymen, and public giving ceremonies are held in churches to make sure that the church members are “accountable” for their tithes and offerings.

It's not to say that Kenya is devoid of people who truly love and serve God. In both America and Kenya-and probably every other place-there will be those few who are truly devoted to their beliefs, and truly serve God with their lives. It is always refreshing to find someone like this, who knows what she believes and actually has it change her life.

But the love for money is such a tricky thing. Money simultaneously is the cause of most of the world's problems, yet the solution to many. Money provides opportunity and comfort, security and guaranteed medical attention. Yet money fosters worry and headache, greed and entitlement.

Many people dismiss religion as a social construction aimed as a money-making machine. In many cases I would have to agree with them. But I would find it difficult to judge those members in the churches who humbly give their tithes as foolish. Perhaps they give to a corrupt religious organization, but for those individuals, their giving shows that money is not their object of worship. Such behavior is commendable.

But money and poverty are knotty subjects. I came to the Peace Corps so that I might understand what poverty was really like. Instead, I am discovering that I will never know the true sting of poverty. I will never know what it is like to choose between purchasing water or food for that day or pray fervently each night that the rains should come. How can I judge anyone for loving money, when it has the power to alleviate basic suffering? How can I convict those who struggle every day with the most basic necessities, when money promises a deep breath from poverty's suffocation?

Just as I will never know what it is really like to be poor, Jesus will never know what it is really like to be human. Jesus knew what hunger was, and he very much tested a human's endurance for physical pain. But Jesus never knew sin. Jesus walked in perfection in God's eyes, and through his deliberate decisions he faced temptations and always came out clean. Never did he feel the blight of evil weighing upon his heart, or feel the hot sensation in his cheeks when a particular moral decision contradicted his conscience. And unlike all of humanity, Jesus never needed a Savior.

So as I continue my work in my village, my growing hair continues to be a reminder of my infantile attempt at self-sacrifice, and the understanding of but a few people of my purpose here.

But this post has nothing to do with my hair. This post is about Jesus Christ. And money.

The Kenyans are highly religious. When coming to Kenya, I did absolutely no background research, so I assumed the religions were tribal and pagan. I expected people to worship the sun god, and during religious gatherings cut themselves to spill their blood on the soil. Instead, I came to find the normal religions: Christianity and Islam. And Christian missionaries hit Kenya especially hard. I can only guess at how it happened: the shiny beacons of hope and light (white people) came with their money and built fancy churches and gave people money and food if they converted to Christianity. So undoubtedly all the starving people were on their knees in front of murals of Jesus Christ.

So as a result, there is no escape from religion in Kenya. On the coast, Muslim dress-code can be seen on every other woman: the flowing black burka concealing any beauty or sensual body curve which God endowed a young woman (in all honesty, I think those mysterious Muslim women are intriguingly beautiful..though I have no way of knowing). On public buses, often a christian pastor will stand in the front aisle and preach for a full-length, hour sermon and then proceed to gather 'offering' from the bus' customers. Angry-sounding pastors gather up their most grizzly voices and shout from the televisions on Sunday mornings, and everyone's customizable ring tones play the latest popular worship song. So there is no question this culture is inundated with religious symbols and rituals, no debate that people could see a poster of someone in a white robe holding a lamb and not instantly think of Jesus.

But back to my hair. The front of it reaches past my eyes, and the back nearly covers my neck entirely. In addition to my unkempt, borderline culturally inappropriate head of hair, my laziness usually allows my goatee to grow for a month or longer. All of that in combination with my caramel, middle-eastern skin makes me closely resemble a certain messiah-- namely Jesus Christ. To confirm this, when visiting the Christian groups at the secondary school, whispers spread like wildfire among the girls as I walked in, saying, “Anafanana na Yesu!” or “He looks like Jesus!”

And in my village, this is how I am treated. People think I am their Savior, that I have come to alleviate them from their poverty and physical suffering. Just like the Jews expected Jesus to be a great political leader who would save them from the Romans, the people in my village expect something so different from me. But Jesus had so much more in mind. He came to save humanity from themselves, to free people from the burdens of their own corruption.

I realize that it is highly arrogant and borderline blasphemous to compare myself to Jesus Christ. Whether you believe He was truly God Himself, an inspirational hippie philosopher, or a fictional character in a giant storybook, I pale in comparison. But upon reflection, my life here in Kenya draws some parallels to Jesus' life on this Earth. To name a few:

Wherever Jesus walked, multitudes would gather around. His mere words stirred inspiration and excitement among his listeners, his knowledge as a child surpassed that of the church leaders, and miracles sparked from his fingertips. Similarly, wherever I walk, people stop what they are doing and shout greetings and welcomes. With my guitar in hand, children flock and gather, eagerly listening to anything I would play. My computer with its internet capabilities gives me an “infinite knowledge,” and with my fancy camera, it is like I miraculously capture life itself.

So in my village there is no doubt I am special. Just my skin color gives me away as something “different,” “exciting” and “worth looking at.” And people's expectations of me are unbounded. In their minds, I am capable of doing everything. One of those main expectations is that of sourcing money from either myself or my wealthy friends, and putting that money into their pockets.

I came, not to give money, but as a medium for people to better their lives. I came to teach whatever I know and to share my life and my experiences to anyone interested. I came to bring a sense of work ethic and empowerment, that through hard work and struggle their lives may be changed. But people want money. They ask me for jobs even after I tell them I am a volunteer, and they ask me to write proposals for them even after I explain why I cannot. The people here see me with the same misunderstanding the Jews had when they saw Jesus. And because I do not offer money, food, or will not take their baby to America with me when I return, I am just as easily dismissed.

But back to religion. When I first arrived in Kenya, I sat through a three-hour church session where people sat in rapt attention, and danced without reservation during the entire period. I was astounded at their stamina and thought to myself how they must really love God and serve Jesus. But the longer I stay, the more I realize people here who call themselves “Christian” or “Muslim” are not really worshiping God. They worship money. They worship all the things that come with money—comfort, status, popularity, sex. They are just like most Americans.

Televangelists preach here in Kenya about wealth in Jesus' name, and America is revered for their prosperity, often to be claimed as a nation “Blessed by God.” A fine, upstanding “Christian” will just as likely double the price in the market to naïve tourists as would their non-religious countrymen, and public giving ceremonies are held in churches to make sure that the church members are “accountable” for their tithes and offerings.

It's not to say that Kenya is devoid of people who truly love and serve God. In both America and Kenya-and probably every other place-there will be those few who are truly devoted to their beliefs, and truly serve God with their lives. It is always refreshing to find someone like this, who knows what she believes and actually has it change her life.

But the love for money is such a tricky thing. Money simultaneously is the cause of most of the world's problems, yet the solution to many. Money provides opportunity and comfort, security and guaranteed medical attention. Yet money fosters worry and headache, greed and entitlement.

Many people dismiss religion as a social construction aimed as a money-making machine. In many cases I would have to agree with them. But I would find it difficult to judge those members in the churches who humbly give their tithes as foolish. Perhaps they give to a corrupt religious organization, but for those individuals, their giving shows that money is not their object of worship. Such behavior is commendable.

But money and poverty are knotty subjects. I came to the Peace Corps so that I might understand what poverty was really like. Instead, I am discovering that I will never know the true sting of poverty. I will never know what it is like to choose between purchasing water or food for that day or pray fervently each night that the rains should come. How can I judge anyone for loving money, when it has the power to alleviate basic suffering? How can I convict those who struggle every day with the most basic necessities, when money promises a deep breath from poverty's suffocation?

Just as I will never know what it is really like to be poor, Jesus will never know what it is really like to be human. Jesus knew what hunger was, and he very much tested a human's endurance for physical pain. But Jesus never knew sin. Jesus walked in perfection in God's eyes, and through his deliberate decisions he faced temptations and always came out clean. Never did he feel the blight of evil weighing upon his heart, or feel the hot sensation in his cheeks when a particular moral decision contradicted his conscience. And unlike all of humanity, Jesus never needed a Savior.

So as I continue my work in my village, my growing hair continues to be a reminder of my infantile attempt at self-sacrifice, and the understanding of but a few people of my purpose here.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)